Look for America

Back in 1993, photographer Kip Harris decided to go with his wife on a trip across the Midwest of America in search of ‘the Heart of the Country’. His images allow us a glimpse of what America looked like 30 years ago, during the first year of the Clinton administration, and his accompanying essay tells us what it felt like.

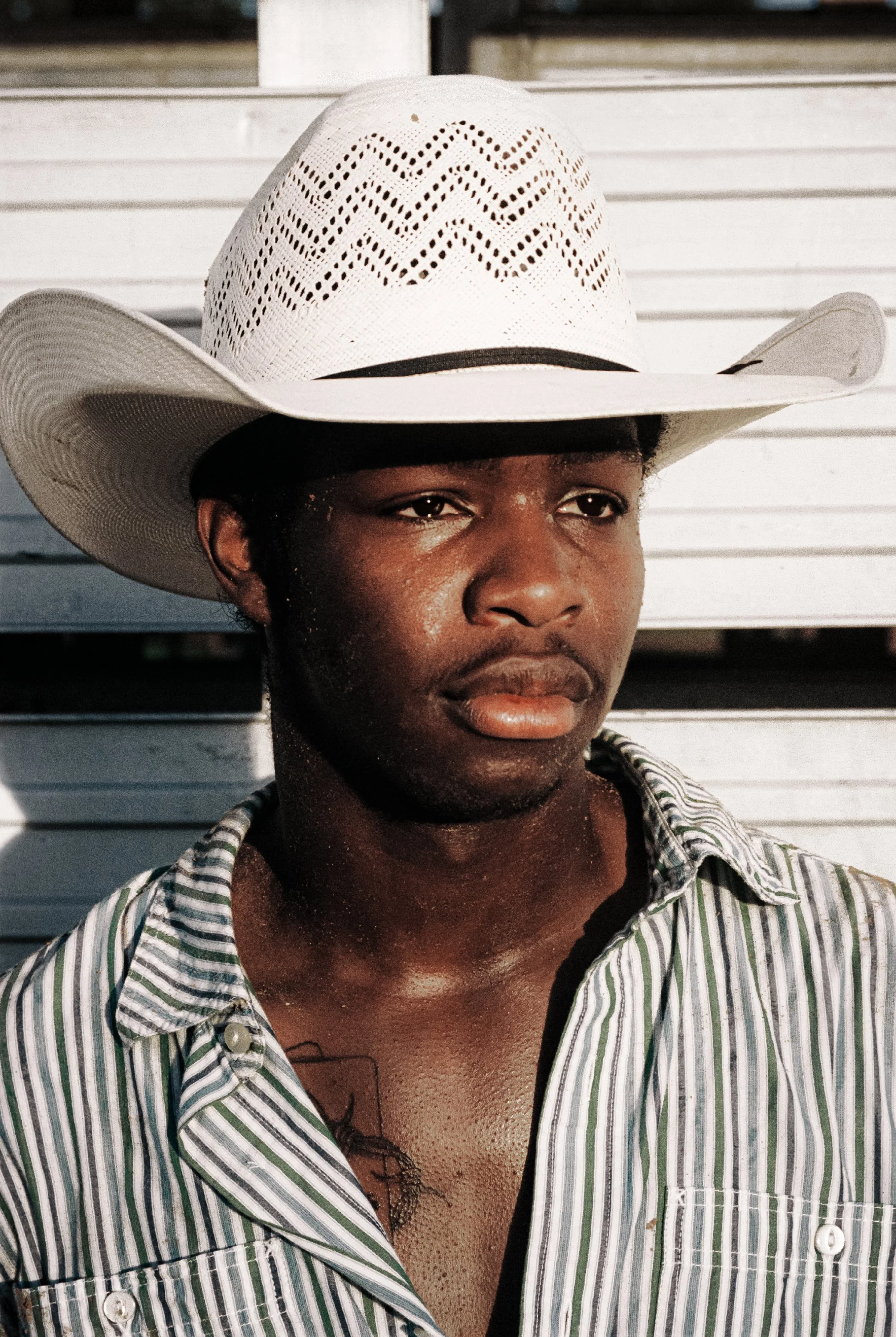

Text and photography Kip HarrisRockville, Indiana ©Kip Harris

In 1993, my wife was working on a novel where a road trip across the Midwest of the US was to be a central feature. She needed to get a feeling for what that would be like. It was a search for “…the Heart of the Heart of the Country,” to borrow a title from William H. Gass, and what the color of the earth was and how it smelled.

Where that “heart” is depends a great deal on where you start. People living in Manhattan think the Midwest starts on the other side of the Hudson as so brilliantly depicted in Saul Steinberg’s “View of the World from 9th Avenue.” People living in Chicago think the Midwest begins just west of Pittsburgh and stretches to maybe Iowa City. For people who live in the Intermountain West, the Midwest begins a little east of Chicago and slowly peters out somewhere west of North Platte.

We decided to fly to Indianapolis after work on the Friday before Thanksgiving and to drive west in a rental car. Our previous individual and collective car trips had always been rushed because we had had places to go: off to college, off on vacation, off to different jobs. We had never taken the time to roam the blue roads across the country and instead had mostly seen freeways and service stations, missing what was life was really like out there.

“We agreed that, in the great American tradition, we would handle this road trip as an adventure, allowing for decisions to be made in the moment and to have no particular agenda ahead of time.”

We agreed that, in the great American tradition, we would handle this road trip as an adventure, allowing for decisions to be made in the moment and to have no particular agenda ahead of time. At an intersection in the road, we would select which way to turn but always tending westward. We wandered through Illinois, Missouri, Iowa, South Dakota, Nebraska, and Wyoming before arriving back home in Salt Lake City. The trip was part William Least Heat-Moon, part Robert Frank, part Jack Kerouac, part American Geography by Matt Black although that book hadn’t yet been written, and part Simon and Garfunkel: “They’ve all come to look for America.”

Hannibal, Missouri ©Kip Harris

Near the Mississippi 1 ©Kip Harris

Near the Mississippi 2 ©Kip Harris

Near the Mississippi 3 ©Kip Harris

Fort Madison, Iowa ©Kip Harris

It was the year of the Great Flood of 1993. One of the strangest aspects of the flooded area was that you could smell the saturated soil and rotting vegetation long before you saw the destruction. Most of the water had receded by the time we drove through but there were places where side roads just disappeared into rank standing water. Buildings / cars / signs were covered in mud. Even shacks built up on stilts showed water stains. One place on the Mississippi that was untouched was Nauvoo, Illinois. Built on the bluff above the River, this village which once rivaled the population of Chicago remained a monument to the careful city planning of its Mormon founders.

“As we drove further west, the flooded land was left behind but we encountered another kind of death. The once thriving small farming towns where proud civic buildings graced the main street were slowly dying.”

As we drove further west, the flooded land was left behind but we encountered another kind of death. The once thriving small farming towns where proud civic buildings graced the main street were slowly dying. The regional Walmart was cheaper than the local grocer, the large high school which serviced several towns could have a real football team and maybe a chemistry class, farm equipment could no longer be repaired by the farmer himself but needed a special tool or part or computer to keep it running, the local theater, once the Friday and Saturday night hang out place, functioned only occasionally if at all. A few civic landmarks still existed: Federal prisons, shared grain elevators, and the local coffee shop or drugstore or sometimes a bowling alley. People still gathered before work or at lunch to talk hog belly futures and church events. These people were increasingly older and less rushed in the smaller towns; younger people were likely to be part of Rotary or the local school board in the larger ones.

This slow death of small town America was more and more obvious as we moved further west. Indiana had a kind of Norman Rockwell feeling of comfort and well being. The farms were well maintained, the buildings were painted, the “Welcome to Our Community” signs were hung with the meeting times for the civic clubs and churches. This became less true as we moved across Iowa.

There we visited Louis Sullivan’s Merchants National Bank in Grinnel, walked about the Amish Community in Kalona where horse pulled carriages waited patiently near parked school buses, spent time roaming around the very strange Shrine of the Grotto of Redemption in West Bend. We had a pizza so saturated with salt that my wife’s face blew up like a balloon the following morning. We stayed mostly in the type of motel made famous or infamous by Nabokov. The ones with the two metal chairs outside each rented room and the telephone booth near the office. We called them Lolita Motels.

Cunningham Drug, Grinnel, Iowa ©Kip Harris

Midwest Iowa Motel, Newton, Iowa ©Kip Harris

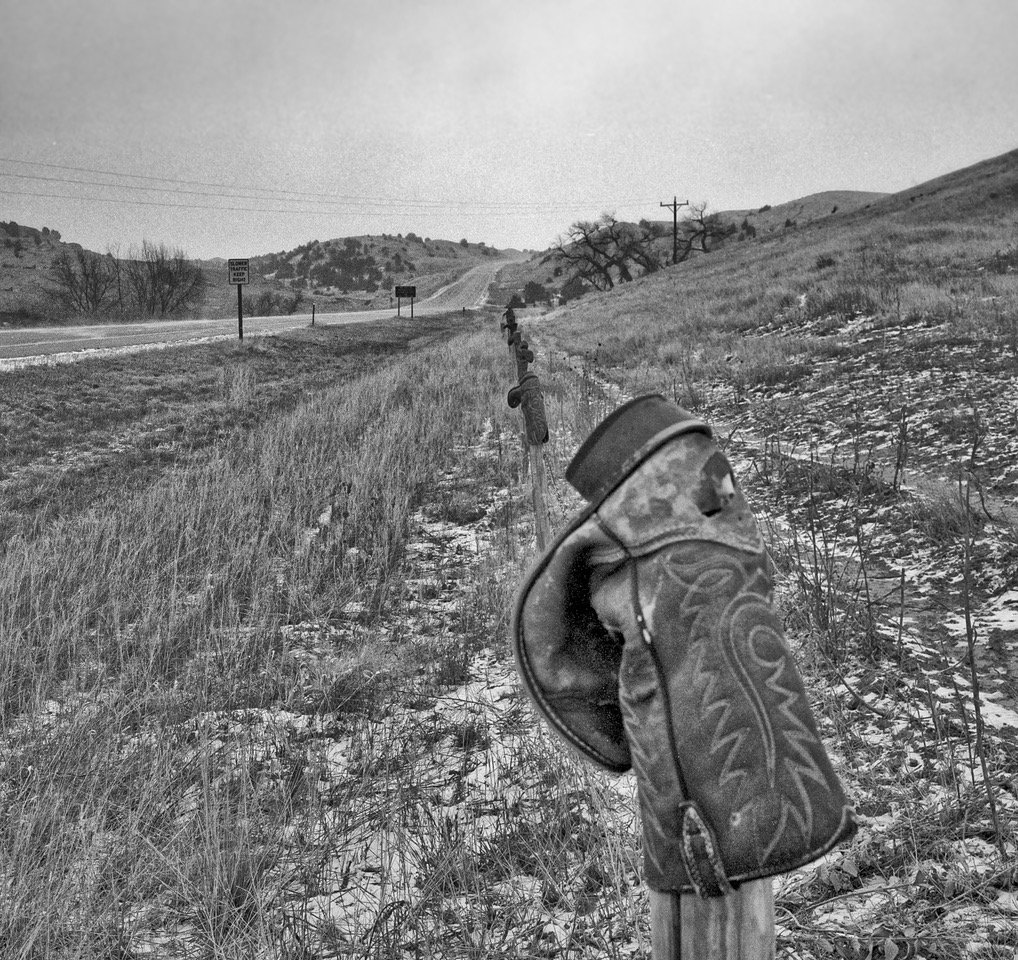

Nebraska Boots ©Kip Harris

Nebraska Road Kill ©Kip Harris

Farm Equipment Junkyard, Nebraska ©Kip Harris

The further west we went the harder it was to pick up NPR on the radio. There were now small town radio stations playing mostly country and western. The ads were for deals at the local truck repair shop and hair dresser. These stations served as a bulletin board for the locals announcing dances and funerals and weddings and bridge clubs. Mostly the kind of community news that used to be printed in the weekly newspapers heavy on scout clubs and high school events while avoiding politics all together.

“We did find Little America in the middle of Wyoming where ice cream cones were 15 cents and the featured lunch entry was liver and onions.”

It was winter by the time we made it into Nebraska. The Winnebago Indian Reservation was nearly snow bound so we missed the game between the Warriors and Lewis and Clark Middle School but did stumble upon perhaps the largest junk yard of farm vehicles anywhere. After a very grim Thanksgiving feast of sliced jellied turkey and canned gravy in the Cedar Bowl in North Platte and being stunned by a mountain of grain waiting for shipment east, we abandoned our plans for more blue highways and returned to the dreaded freeways. We did find Little America in the middle of Wyoming where ice cream cones were 15 cents and the featured lunch entry was liver and onions. The waitresses were middle aged and called you “dear” or “honey” and always got the order correct.

What we discovered during that trip was most succinctly stated by Mark Power: “America continues to enthrall and to disappoint in equal measure.”

North Platte, Nebraska ©Kip Harris

About Kip Harris

Harris grew up in a small farming community in Idaho. He holds degrees in English literature from Dartmouth College, in humanities from the University of Chicago, and architecture from the University of Utah. He was a principal of FFKR Architects in Salt Lake City for nearly 30 years.

A serious photographer since the late 80s, he has exhibited in the United States, Canada, Australia, and Europe. He has been published in Shots Magazine, The Photo Review, Art Reveal, Smithsonian.com, Street Photography Magazine, Barren Magazine, Tagree, Square, Black and White (cover) and a number of on-line photographic sites.

To see more of his work, visit his website or follow him on Instagram