Icons: Richard Avedon

Avedon’s stark portraits provided unbiased and humanising glimpses of the most influential sociopolitical figures of the 20th century. But can work based around such figures be as non-political as Avedon claims it to be?

Text Tom Wyche Unlike other photographers written about for our ICONS series, Richard Avedon wasn’t necessarily driven to photography like those who stumbled upon it as their ideal medium were. Photography was instead a sort of unintentional constant of his life, where the instinct to take photos followed him from so young that a photographic career was inevitable. To this effect the first photo Avedon ever “printed” was on his burnt skin, taping a negative portrait of his sister to his shoulder and letting the sun burn the resulting image onto him.

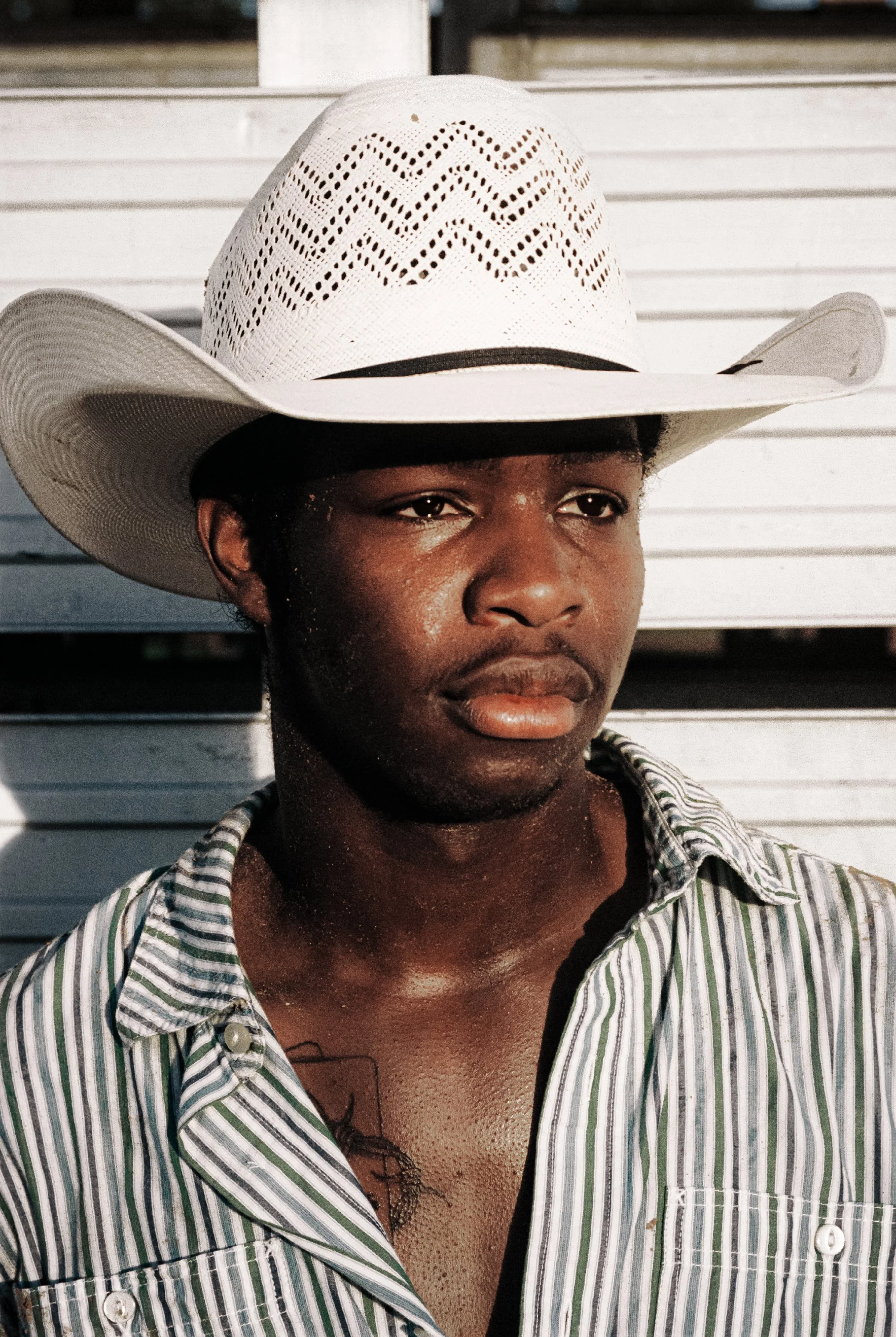

.James Story, Coal Miner – 1979

Duke Ellington – 1965

After joining the Young Men’s Hebrew Association camera club as a child, he went on to serve as Photographer’s mate in the Second World War, photographing merchant marine soldiers for their ID cards. Only after this did he begin to actually identify as a photographer, still however keeping this as a mostly commercial title, beginning at Harper’s Bazaar primarily as an advertising photographer.

“My job was to do identity photographs. I must have taken pictures of one hundred thousand faces before it occurred to me I was becoming a photographer."

Harper’s Bazaar – 1948

Harper’s Bazaar – 1965

Avedon of course famously worked his way up to lead photographer of the magazine, but this incidental, casual relationship with photography gave him a unique eye and focus within the medium that is just so immediately striking.

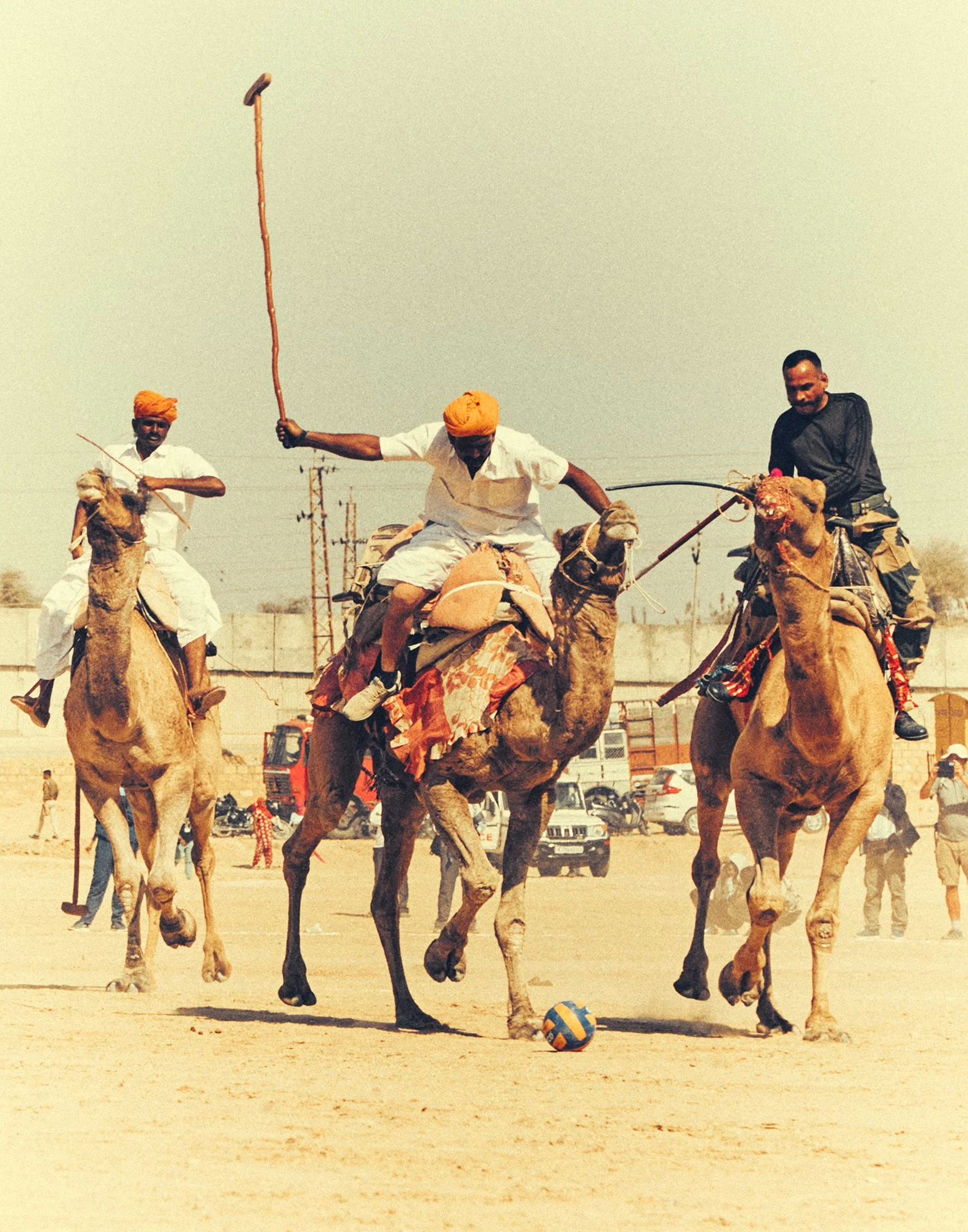

Student Non-Violent coordinating committee, headed by Julien Bond – 1963

There’s this apparentness to Avedon’s work that seemed to come from this constant presence of photography in his life, and as a result, an interaction with his subjects that just feels so natural. The innovation of Avedon’s photographic style was the casual, human nature of the models shown. While having your subjects actually emote, both within artistic and commercial photography is obviously a given nowadays, it can’t be stressed enough how profoundly noticeable this change forwarded by Avedon was. A 1952 New Yorker article written about his work poetically described this new style of photographing models as: “She laughed, danced, skated, gambolled among herds of elephants, sang in the rain, ran breathlessly down the Champs-Elysées, smiled and sipped cognac at café tables, and otherwise gave evidence of being human.”

Umbrella girl – 1957

Dovima with elephants – 1955

Killer Joe Piro – 1962

“My photographs don’t go below the surface. I have great faith in surfaces. A good one is full of clues.”

Avedon has this progressively blasé persona and attitude to his subjects that not only heightens this sense of comfortability in his photography, but presumes acceptance in the world surrounding it. He was political in a particular way, having progressive beliefs that he adamantly fought for outside of photography that, while also evident in his work, he distanced himself from multiple times. One of the most known examples of this is when Avedon was asked directly about the political nature of his 1976 work “The family”, in which he photographed politicians during the election year, stating that:

"I feel nothing at all for the majority of these people.''

The Family – 1976

Specialist John R. Copeland – 2004

Simultaneously, he was also jailed a few years prior for participating in rallies against the Vietnam war after travelling to Vietnam as a war correspondent, subsequently creating work about both events he has spoken about since as expressly political.

“I just felt rage seeing them there like that, in that place. I feel only rage toward young men who allow themselves to be put in that position without any idea of what they're doing and why they are doing it. This is the punishment for mindlessness. And the punishment can be their lives.”

These might seem like unavoidably contradictory beliefs, but I think the meaning of this within Avedon’s total body of work comes back to the aforementioned personal nature of his early portrait work. His work was always political, even if unintentionally so. He left Harper’s Bazaar in 1965 for example after a shoot he’d done that featured models of colour caused an unexpected wave of controversy, leaving to instead work for Vogue for the following 20 years.

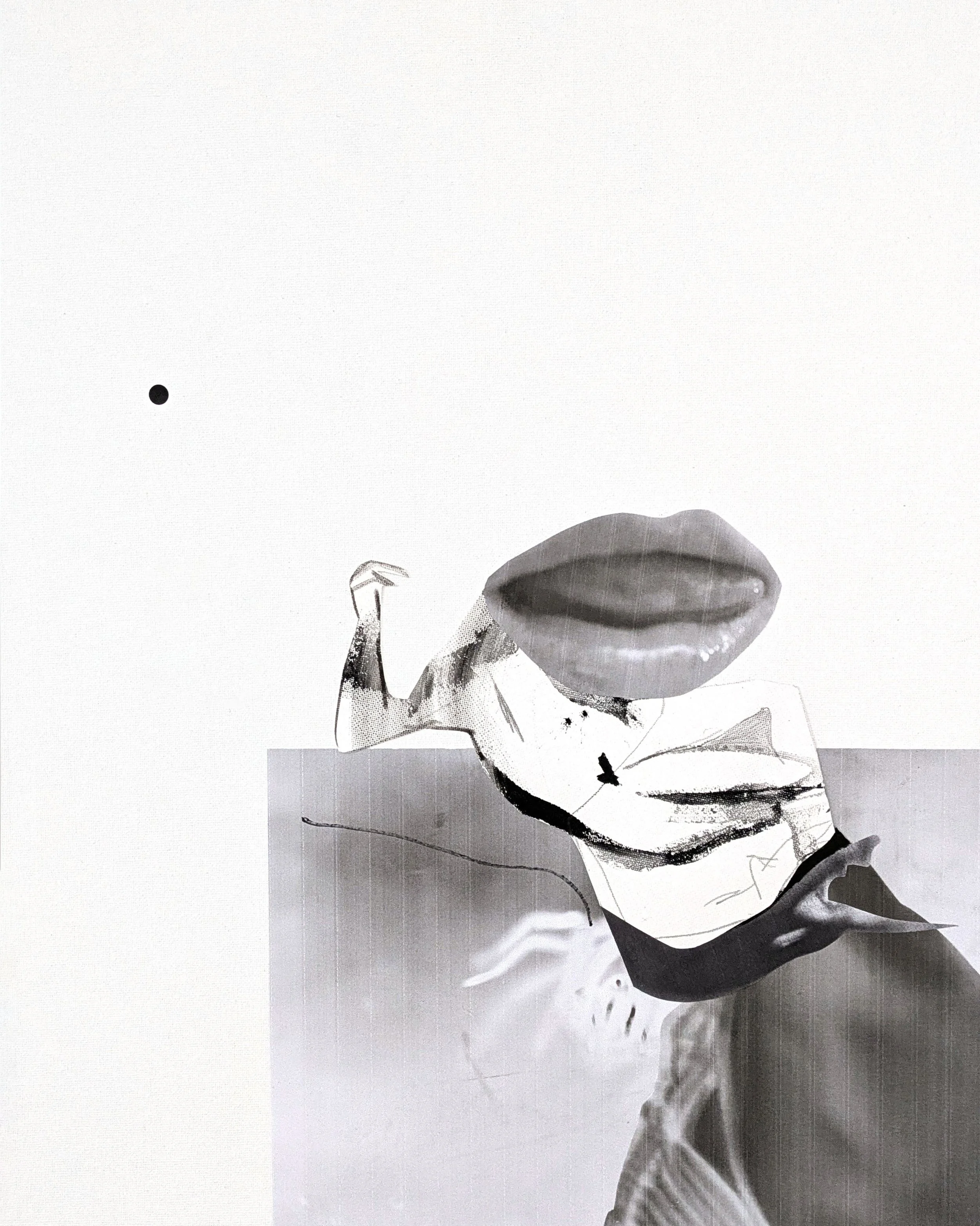

EGOÏSTE NO.13 – 1997

I think this shows that while the statements made by his photos are certainly political, this isn't done with the intention of forwarding or promoting his specific beliefs, instead acting as a reflection of how the world (for better or for worse) appears through Avedon’s eyes. His photos of Vietnamese soldiers aren’t so much a call to action as they are Avedon capturing how heartbreaking it is for him to watch this happen in real time. To this effect, Avedon himself has said multiple times:

“My portraits are more about me than they are about the people I photograph.”

Napalm Victim – 1971

William Casby, Born in Slavery – 1963

This perspective makes his portrait work absolutely fascinating. From even the 50’s Avedon had reached a level of notoriety where he’d photographed figures as enduring as Marilyn Monroe and JFK, even maintaining this reputation to a point where he photographed Obama in the 2000’s. This aforementioned indifference to the status of those he photographed creates this remarkably untainted personal perspective of celebrities that no one else could see unless shown by Avedon. Black and white portraits of Malcolm X and Audrey Hepburn are as stripped back and plain as the ID photos Avedon used to take of soldiers in both WW2 and Korea decades prior, even using a remarkably similar set up and framing for these vastly different people.

Audrey Hepburn – 1953

Malcolm X, Black Nationalist Leader, New York – 1963

Barack Obama – 2004

What is created as a result are these intensely humanising portraits. His work isn’t ever about proving anything specific about the subject, but purely capturing exactly how Avedon sees these people, regardless of whether or not that feeling is political.

“A portrait is not a likeness. The moment an emotion or fact is transformed into a photograph it is no longer a fact but an opinion. There is no such thing as inaccuracy in a photograph. All photographs are accurate. None of them is the truth.”

About Richard Avedon

Avedon was born on May 15th, 1923 in New York. He’s won over 15 photographic awards over the course of his career, inlcuding the Royal Photographic Society’s 150th Anniversary Medal and the National Arts award for Lifetime Achievement in 2003.

He passed away on October 1st, 2004, in Texas while shooting an assignment for The New Yorker. It was released unfinished a month after his death.

If you want to learn more about Richard Avedon, the Avedon Foundation offers an incredibly comprehensive view of his work. You can follow them on Instagram as well.