Icons: Bob Richardson

A look at how Richardson’s lost photos and repeated self destruction impacted his career, and how he introduced theatricality to fashion photography.

Text Tom Wyche Bob Richardson, (uncredited)

Bob Richardson’s pervasive self destruction has been chronicled to a degree that it’s now almost difficult to discuss his truly subversive work in fashion photography without immediately being distracted by the gossip of his various blow-outs and tumultuous personal life. However, the two are so intrinsically linked in their codependent impact that it’s hard to see the effect one had on the other, or the outside world, without acknowledgement of it.

“That Bob Richardson was commissioned for Brides is like finding Charles Manson serving fairy cakes in a tea shop.”

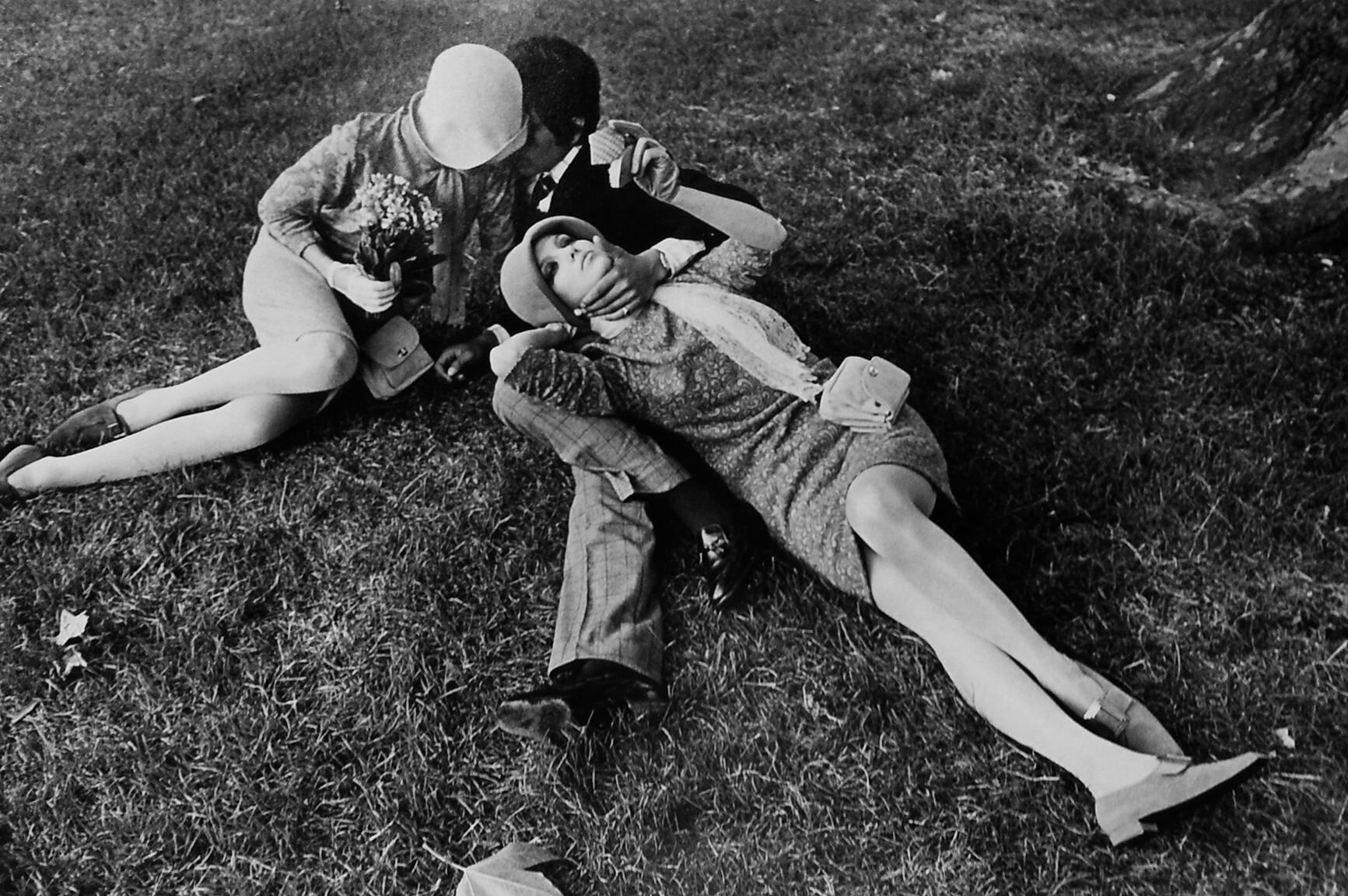

Donna Mitchell and friends, London, Vogue, 1965

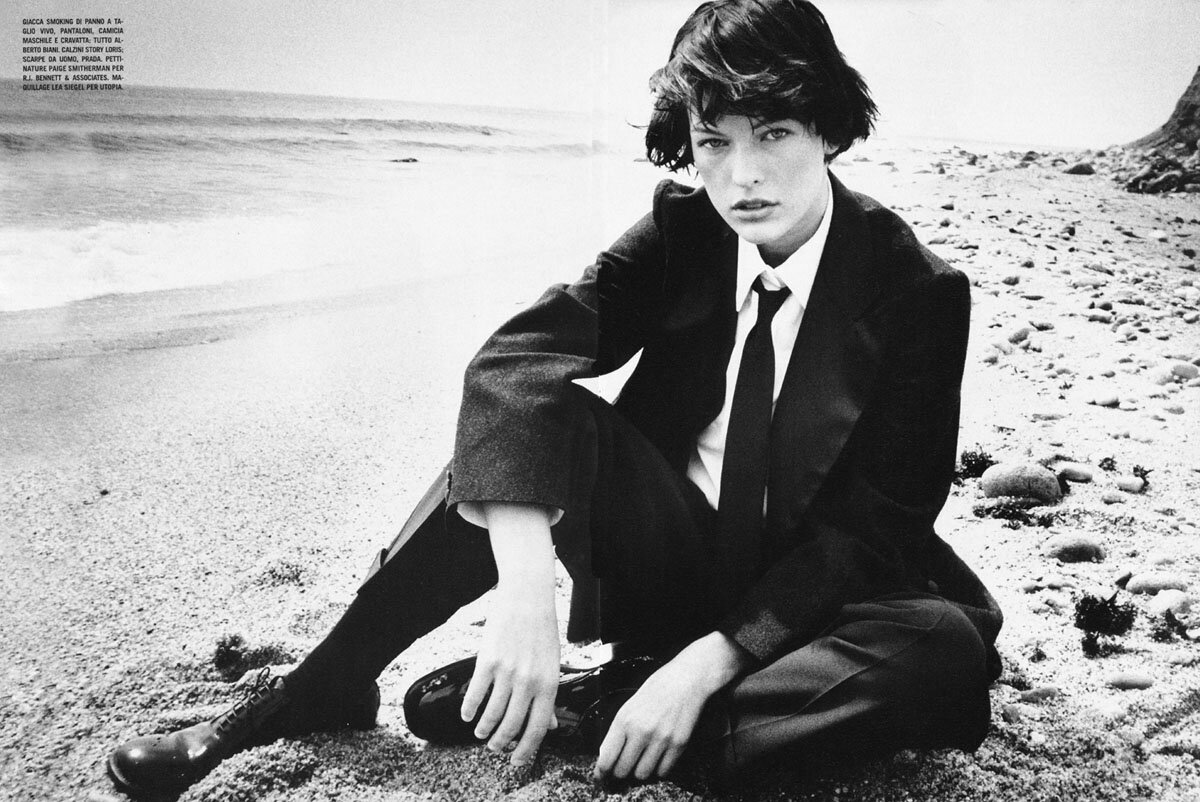

Milla Jovovich Vogue UK, 1997

His work, primarily featured in Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue throughout the 60s and early 70s, showed a drama and an honest exposure that hadn’t existed in fashion and commercial photography at the time. Yet, because of a combination of ego and an immense self deprecation, much of this work has not been preserved and doesn’t exist anymore, giving the wrong impression that his extremely successful and notable career was relatively short lived. This is either from falling through the cracks of archival practice due to the magazines not being saved/ negatives being lost, or the work actively destroyed by Bob after distancing himself from his own work. Meeting Bob after the re-discovery of his work in the 90s, art historian Martin Harrison said this of Bob reacting to seeing his own work again.

“After a while, I pulled out some photocopies of his work, and he’d say things like ‘God, I was awful’. But mixed in with the self deprecation was a definite sense of professional self esteem.”

Anjelica Huston, Vogue Paris, 1972

His work was characterized by this juxtaposition between unabashed reality combined with an almost theatrical staging, creating a heightened but realistic sense of drama. His photos showed melodrama, but melodrama that sincerely reflected how tumultuous and emotional these people’s lives sincerely were. This can be looked back at as simply a depiction of the public fascination with the “sex, drugs and rock “n” roll” mantra of artist of the 60’s and 70’s, but to attribute Bob’s work to this feels like a reduction. Admittedly Bob is explicitly quoted as describing his own work like this, but what separates him from other photographers of the time is the depth that exists beyond this facet of his work. This is shown within Richardson’s most famous shoot, photographing Donna Mitchell on a Greek beach for French Vogue in the late 60’s.

“She is seen dancing with abandon in the Babulas Taverna, in Rhodes; she contemplates candles in a church; plays with a naked toddler (a young Terry Richardson, Bob’s son) [...] In one of the shots, Mitchell is crying on the beach. The overwhelming impression is of deep emotion and passion – a sense of reality, sex, joy, loneliness and broken trust.”

Donna Mitchell, Vogue Paris, 1967

Vogue Italy, 1972

What’s shown isn’t a glorification of that lifestyle, but instead an honest depiction of the freedom that lifestyle held, and the highs and lows that freedom brought with it. Alongside this there was a definite element of shock in his work that caused him to stand out. In some cases a certainly reactionary decision and in others a sincere, unintentionally provocative part of his photography that conversely was a result of a sincere depiction of the life he lived. Photos of the former are surprisingly politically charged, an example of which being a 1969 Irish series he photographed during his period at French Vogue, with his then partner, Anjelica Huston.

“I remember an Irish series we did for French Vogue. He had me flung over the side of a bridge, carrying a gun, with blood coming from my chest. This was when the I.R.A. was in full force. His pictures always had a subtext – they were about his state of mind, about him.”

Another example of this from a few years on featured Huston with a Nazi lover in Rome, with the intention of drawing out as much discomfort as he could from all involved. This shock value was certainly reflective of Bob’s proclivity for confrontation and its effect on the professional relationships he held with those around him, leaving Harper’s Bazaar after this confrontational streak led to consistent clashes with colleagues and editors. This affected his reputation to a degree where in 1967 he left for Europe to instead work at French Vogue, which gave him the freedom to shoot scenarios as described above. Neither the confrontational personality or shooting style came first, both instead reflected and only served to heighten the other. Throughout this period Richardson’s personal life suffered, leading to his tumble out of photography into homelessness that followed from his split from Huston. To call their relationship tumultuous would be an understatement, with Richardson’s struggles with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia leading him to violently lash out at Huston, often followed by a retreat into himself.

Anjelica Huston, 1971

Donna Mitchell and Alexis von Waldeck, Vogue Paris, 1967

It is of vital importance when discussing Richardson and figures like him not to romanticize or pardon behaviors like these under the myth of viewing him as a troubled creative. While his work was certainly impactful, it is also imperative to state in the plainest terms possible that he was abusive, and lashed out at those close to him consistently. This shouldn’t be brushed aside or understated just to praise his work in a more palatable way. When remembering Richardson, you must do it with honesty about how his status allowed him to get away with being an abuser.

Richardson and Huston’s inevitable split was the beginning of his fall off the edge, when his following isolation caused his spark for photography to disappear.

Milla Jovovich + Bob Richardson, (uncredited)

Anjelica Huston US Vogue, 1969

“I kept going for years, but I had lost interest – it vanished [...] It was like waking up one morning and finding yourself all alone and wondering what you’re going to do. In the end, I just gave up. I’d been taking lousy photographs, and I didn’t want to work anymore. I think I wanted to find out if I wanted to live.”

Donna Mitchell, Vogue UK, 1966

As stated he continued taking photos for a majority of the 70’s with little passion, and disappeared to California around the turn of the new decade to leave photography and fade away from the scene that had consumed him. His struggles with drugs and increasingly unmanageable schizophrenia caused him to fall into homelessness and subsequently lose the majority of his body of work that had been so revolutionary previously. Richardson spent much of this time sleeping on the street and on California beaches, reaching a point of instability and self medication that he believed people on television to speak directly to him. Despite this period of extreme hardship however, around the late 80’s he began to recover, finding a job delivering flowers and living again in anonymity. While his 1991 rediscovery by the art historian mentioned previously led to a second wave of his work, and a renewed interest in it, It seems he still hadn’t changed much in behavior from his confrontational, abusive past.

“The Bob Richardson we met that day was a gentle, toothless old man who was into astrology and who craved to be recognized as the great fashion photographer.”

This is contrast with when the same reporter met Bob in New York several months later

“The Bob we met in Terry's studio was the Bob we had been warned about. Confrontational and impossible to work with, this was the Bob Richardson who was his own worst enemy.”

Anjelica Huston, 1971

Vogue, 1968

About Bob Richardson

Bob Richardson was born in Long Island, New York on January 3rd, 1928, training as a graphic designer before taking up photography at 35.

His son, Terry Richardson, also works as a successful fashion photographer. Terry’s work has been featured in Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue, alongside GQ. He’s had as successful a career as his father.

Collections of Bob Richardson’s work are hard to locate for reasons mentioned previously, but to learn more either buy his book or find more about his re-emergence in the 90’s here.